Research shows that when presented a list of leadership actions, people easily designate them by gender. Look at the following list, and I suspect you too will be able to quickly categorize them as masculine or feminine.

- Command

- Compete

- Collaborate

- Nurture

- Communicate

- Emote

- Direct

- Assert

- Relate

Crossing gender lines is fraught with social peril. Female leaders who command are called names I can’t print. Men who emote are seen as weak and ineffectual. Which brings us to the classic question: Are gender differences genetic or learned? Nature or nurture? Hardwired or socially scripted? Scientists have struggled with this question for centuries. I don’t have the answer, but I do have some observations based on the statistical concept I call the tyranny of the tails that may provide some insight.

Observation 1: Gender differences show up the most in the extremes

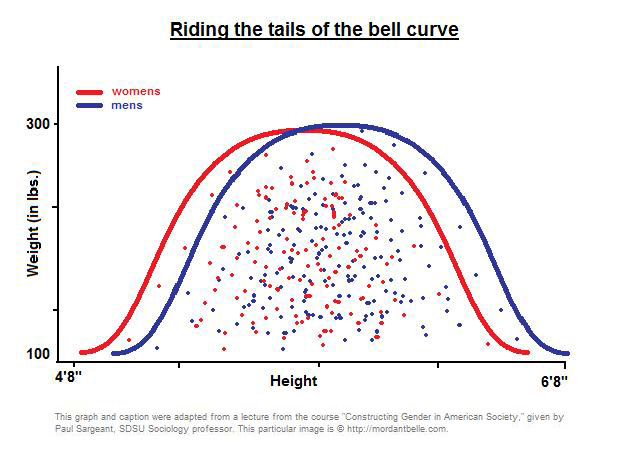

Let us use height to make the illustration, which is easy to measure. Whether you quantify the heights of men and women by observation or by careful scientific study, the conclusion is the same. Women, as a whole, are shorter than men. No matter the country, men have a height advantage. The average height of a man in the United States is 5’10”; for a women it is 5”5”. It is fair to say that generally the tallest people in the room will be male and the shortest will be female.

While true, it is also true that there is great overlap in the mid ranges across genders. I know lots of men and women in the 5”6” to 5”8” ranges. It is only at the extremes of height that men are more likely to be represented for tall and women for short. Most men and women fall smack dab in the middle.

There is great overlap in the two bell curves – and it is at the extremes that the biggest differentiators show up. Most of us, men and women, fall between 5 feet and 6 feet – and the bell curve shows us that men and women are more alike than different.

Observation 2: We simplify as a survival strategy.

We are confronted with a dazzling array of data and sensory experiences. It is far easier to create two categories (tall/short) than a myriad of them. It takes much less brain power to generalize and say that men are tall and women are short.

Observation 3: This simplification creates stereotypes that may be true in the aggregate, but can undermine the individual.

Tall women may find it difficult to date shorter men, as there is a social view that the man should be the taller one (and it is somewhat embarrassing to both if the woman is taller). Short men are not always seen as masculine as taller ones. We even have a name for this: the Napoleon complex or short man syndrome.

Observation 4: We begin to link these gross generalizations tighter in ways that defy logic.

Taller men have a selection advantage when vying for positions of leadership due to this. Here is an example of how our flawed (and subconscious) thought process works: tall men are seen as more able leaders, even though height has little to do with leadership itself, only our perception of masculinity and leadership.

- Men are tall

- Leadership is a male domain

- Therefore, tall men must be better leaders

Observation 5: In reality, most human traits appear in a range.

There are hyper-competitive folks, and extremely non-competitive folks – but most of us fall somewhere in the middle, both male and female. Competitiveness (or any other trait) may have a slight gender bias, but is not gender exclusive.

This is the tyranny of the tails… when we attribute gross characteristics of a large population to everyone within it – and do not acknowledge individual variation or that the range of “normal” encompasses far more. While we are more alike than different, we differentiate based on the extremes. This may be a shortcut, but it leads to faulty conclusions, actions and characterizations.

So I encourage my competitive female friends and my empathic male friends, and others I know who defy narrowly defined gender stereotypes, to claim who they are. And I challenge each of us to recognize when our thinking is flawed by the tyranny of the tails and then to step back, readjust, and get a clearer view – even if it might be a bit more complex and individualistic.

Where has the tyranny of the tails tripped you up?

3 Responses

hanks Kris for incorporating variation into your discussion of leadership. Variation exists all around us. Understanding variation is the key to improving not only our perceptions of people, but improving our work processes. We apply the same thought processes you mention to our work processes and make decisions based on the tails and not the whole performance of the process!

This is great! I’ve heard the brain called a “fuzzy pattern recognizer.” We see these traits in leadership now (height, size, gender, etc.), which are probably holdovers from more violent times, and we think they’re valid patterns. When we prop up leaders because of characteristics that have nothing to do with their actual ability to lead, we’re filling space that could be occupied by someone better suited.

That bell curve graph is completely made up. Those two statistics would not produce a bell curve at all, but rather two linear maps that increased simultaneously along both axis’. Unfortunately for this article, you would find that the male curve would be greater in both values in its entirety. You can simply Google human height and weight by gender to find this. This “Riding the tail end of the bell curve” graph is a fallacy.

Comments are closed.