I’m up to my eyeballs in complexity. Yes, we all are. Our “modern” world is a fast-paced, interconnected, technologically driven superhighway.

Yet my immersion in complexity is one I’ve chosen. Helping clients struggling with complex issues is how I earn a living.

For example, I partner with clients who are doing things like:

- Sparking innovation into staid organizations

- Rethinking higher education

- Finding ways to make health care accessible to all

- Shifting decades-old cultural norms into the 21st century

Interesting work. Challenging work. Complex work.

These are not linear, single-cause situations. These are interdependent, entangled situations that don’t have a playbook, road map, or textbook for their specific situation. We are figuring it out as we go. Or, as my colleague Brian says, we are building an experimental plane while in mid-air and flight.

Warning: I’ve been doing one of my geeky deep dives into the current thinking on complexity. I’ve been consuming the Incerto Series by Nassim Nicholas Taleb. I’ve been in multiple discussions with two peers, Joe Indiano and Chad Miller on Dave Snowden’s Cynafin framework.

To your great relief, I’ll not bore you with any of that. I will first share some thoughts on how you know when you are dealing with complexity (and not just a troublesome problem) – and some practical examples of approaches that work for me.

A definition of complexity from Taleb:

Complex systems are full of interdependencies – some hard to detect. None are linear. It is hard to see how things work by looking at a single response. Manmade complex systems tend to develop cascades and runaway chains of reactions that decrease, even eliminate, predictability and cause outsized events.

When we experience complexity (things we can’t predict), we fear it and overreact. It is our fears and thirst for order that cause us to try to force things into linear and causal relationships.

When you are working in a system experiencing complexity, it will require something very different than linear or simpler problems. And so, when you find yourself trying to force a solution or are frustrated because no matter what you do doesn’t seem to work, take a step back and consider if you are indeed in complexity and need to do something differently.

Tip One: Create an Imperfect but Helpful Model

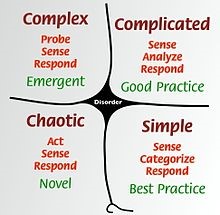

My very first tip in dealing with complexity is to find a model or framework that can help you make sense of the situation. And Snowden does just that with his Cynafin framework (created in 1999 for IBM).

Snowden describes his framework as a “sense-making device.” Models and frameworks are all imperfect and over-generalized, but they are invaluable in helping us communicate and explore ideas and events. The framework above, while simple, has helped a team I’m working on to understand why our approach with a client project was falling short and what we might do differently.

This framework (and others) may take years to refine and hundreds of pages to describe. Yet creating a crisp graphic can enable novices like me to grasp the essence quickly and in useful ways.

Tip Two: Know When you are In Complexity

There are situations where the problem is simple (been there/done that). There is a proven approach, and you just need to apply it. Other situations are complicated (it’s hard, but there is an analytical way to tackle it – think chess). Complex situations are when the unknowns are unknown. The answers only become apparent in retrospect and through probing and experimentation (think solving a complex murder case).

When you are clear that you have entered complexity, you can move into a much more appropriate response. You can also stop trying to force a simple or linear solution and spend your energy elsewhere.

Tip Three: Define the Best Possible Outcome

I still vividly recall a coaching conversation where my client (we’ll call him Sam) was trying (to no avail) to get my help in turning a complex situation into a simple one. We were preparing him to have a difficult and important conversation at a church board of trustees meeting. There were going to be twelve people sitting around the table. The topic was emotional. There were political forces at play. Some relationships were frayed. Sam was charged with broaching the topic, and he was much more comfortable talking about finances and spreadsheets than feelings and interpersonal conflicts.

We spent a frustrating (for both of us) thirty minutes attempting to script the conversation:

- “What should I say first?”

- Then, “I think Sue will reply by saying this. What should I say then?”

- Then, “What happens if Bill is not there? It will change the dynamic. What should I say then?”

- Then, “If Yolanda gets teary, what should I do?”

And on and on and on. I think you get the drift. Sam was hoping for a play-by play, planned in advance, guide to the conversation. Which to his credit, he would have diligently practiced and memorized.

The problem is that he was in complexity. Lots of possible responses, but they were not predictable. A conversation that had no history, so everyone was in unchartered territory.

Here is what we did instead. We focused on describing the best possible outcome for the meeting. He quickly created a list that included: We get this issue on the table. Everyone has a voice. Everyone is respected. We talk about different options. We have a plan to continue the discussion.

Bingo! He could set up the conversation rather than direct it. He could share a framework for the conversation (ground rules). Then he could let the conversation unfold and respond rather than regulate.

By defining a good outcome (no matter if you don’t know HOW you’ll get there), you can wade into complexity with a guiding star. In complexity, articulating the best possible outcomes puts more focus on the process and less on the procedure.

Tip Four: Get Quiet

I think that it is NOT a coincidence that there is much more interest in mindfulness now. There is a bit of paradox: the faster things go, the more we need to slow down. With clear heads, we have the cognitive wherewithal to tackle complexity. The quote “Still waters run deep” reminds us that when we can still ourselves, we can go deep. And complexity requires us to be clear-headed, open-eyed, and with enough emotional bandwidth to navigate unknown territory.

When you are quiet and focused, patterns appear. You see things that you miss in hurry and scurry. You take measured action rather than just any action for the sake of taking action.

For me, getting quiet looks like 45 minutes in the morning to journal, meditate, and read. For others, it is to take a break at midday for exercise or a nap. Other peers do yoga or have a meditation group.

However you approach it, when you are in the midst of complexity, you are well served to stop doing and just sit with it a bit.

I’m curious to hear the tips that help you navigate complexity. Please share!